Molly Ivins wrote lively, graceful tributes to other people, individuals she genuinely admired for courage and for service to the public

Monthly Archives: January 2007

Libby defense attempts win-win with incomplete memory of government witnesses

The testimony of three prosecution witnesses in the Libby trial has now placed Lewis Libby, as Vice President Cheney

Prolonging Vietnam, part 2: why was the Watergate bugged?

Prolonging

The secrecy, manipulation and deceit of the Nixon years had no larger foci than the two consuming topics of

Nixon knew how unpopular the Vietnam War was, and against this backdrop of

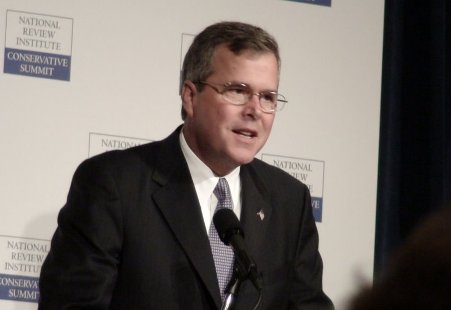

Iraq escalation benefits only Jeb Bush

Iraq escalation benefits only Jeb Bush

Senator McCain presents as someone who figures it’s his turn, per

generally the way GOP presidential nominations work—the next man in

line steps up, wins the nomination usually without too much difficulty,

and then wins or loses the general election. The occasional exception

like Barry Goldwater is characterized for a generation in party lore as

someone who tore the party apart and then went on to lose the

presidential election in a landslide. McCain is showing his loyalty in

spades to the Bush team, to the Oval Office. But only some obliviousness

to history would predict that his loyalty will be repaid with unstinting

support by Team Bush.

McCain

There can be no happy Iraq outcome for McCain. If things get worse–the overwhelming probability–then even he will be forced to bail on

the policy at some point, and the question will always be why he did not

do so earlier, saving more lives; why he did not put his independent

power base to better use. He will be associated with, and he is

aggressively associating himself with, catastrophe. If things were by

some miracle to get better, the Iraq War is still Bush’s war. Meanwhile,

Governor Jeb Bush sits comfortably by in Florida, in relative political

safety in spite of Mark Foley, the sugar growers, his family’s several

run-ins with the law, the ecological disaster in the Everglades, and the

ongoing election fraud in Florida. Jeb Bush is not tied to Iraq policy;

he has no son in Iraq; he is not storming the country in support of

Bush’s escalation.

Jeb Bush

White House Iraq policy at this point, in other words, may be guided by

desire to help Jeb win next time. This is the only perspective from

which the escalation makes even bad sense.

Of course, a plausible alternative explanation is that it makes no sense

at all—that it is merely Bush’s vain effort to prolong the war, which

is what he cares about most, while his cronies with both hands in the

cookie jar frantically extract their utmost.

Iraq escalation benefits only Jeb Bush

It is difficult to imagine the sane person who could imagine that supporting the Bush escalation in

What prolonged the Vietnam War?

What prolonged the Vietnam War?

- Nixon with Kissinger

Diaries of Nixon’s White House Chief of Staff, H. R. Haldeman, demonstrate that Nixon was fully aware in election year 1972 that the Vietnam War was not popular. The White House turned a paranoiac, watchful eye ever outward, constantly alert, scanning the political zodiac for any sign that the Democrats were going to capitalize on the unpopularity of the war.

Nixon came into the White House knowing he would not have won in 1968 had Robert F. Kennedy, his campaign rocket-propelled by opposition to the war as well as by the Kennedy mystique, not been assassinated; had Lyndon Johnson’s Vice President Hubert Humphrey not been inextricably tied to Vietnam; and had the early and effective opposition to the war by Eugene McCarthy not been derailed by RFK. The history of the Sixties is partly a series of flukes, had they not been tragic; a series of near-misses that narrowly avoided ending the Vietnam War on the larger scale and the political career of Richard M. Nixon among others on the smaller. At any moment the nation had the potential to rise up in organized, spontaneous political action to break the stranglehold of Vietnam.

- RFK

Nixon knew it. Even the impossibly late entry into the 1968 nominating process of George McGovern, hero to the young, helped fuel the passion against Nixon and the war; even with opponents of the Vietnam War hopelessly split, there was such a Democratic reenergizing in the last few weeks and especially the last days of the 1968 campaign that Hubert Horatio Humphrey almost managed to squeak out a win. Citizens who had at long last turned away their scrutiny from LBJ and focused it on Nixon and Agnew got so motivated, or so steamed, that in some places HHH came into respectful treatment as a candidate that he scarcely received at the time he was nominated. At the start of his campaign, Humphrey could hardly get paid attention. At the end, there was such a surge that ordinary donors were literally throwing money–tens, small bills–at him or his people in personal appearances; his volunteers were opening hastily sealed envelopes of miscellaneous sizes and stationery, into which money had been thrust without request for receipt or sometimes even a note, sent via regular mail.

Unfortunately the Democratic Party of the time never did adequately focus on and oppose the Vietnam War, not in an adequately organized way, and historians are free to wonder why not. One cause was certainly the grief, fear and demoralization brought about by the assassinations of John Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy. (It is Orwellian that those murders, which did so much to wound and cripple the Democrats, have been vaguely blamed on some culture of Sixties permissiveness.) Another cause was the lack of a blocking agent, as John Stuart Mill would put it, in that the press was as usual royalist and timid in scrutinizing the actions of presidents in conducting war. (Regarding Vietnam, the press was additionally confused by a gullible view that Henry Kissinger would bring about peace if Nixon would let him.) Undoubtedly another cause was White House manipulation of internal Democratic Party politics, using tactics including bribery and assisted by several prominent personalities of the time including John Connally, Billy Graham and George Wallace.

But the war was always present, and opposition to the war was growing daily. One did not have to start from any particular spot on the political spectrum. When combat veterans started coming home from Vietnam by the thousands, if alive and relatively healthy they came home with a single, lucid, across-the-board recognition that many of them had acquired within a few minutes in Southeast Asia: “nobody [back home] knew anything.” The recognition did not necessarily translate into instantaneous and organized opposition, but it did translate into solid, bedrock, widespread lack of enthusiasm. That, in other words, was square one – not among draft resisters and war opponents but among people who had gone, and their relatives and acquaintance. Anecdotes about fragging First Lieutenants will do that.

Nixon knew it, and took steps accordingly.

Over the next few weeks, we in our time will be facing a chief executive bent more than Nixon was on prolonging and expanding a war. As always when there is heavy rightwing rhetoric on “moving forward,” we have to look backward to some extent for guidance on the tactics that will be used. Forewarned is forearmed.

The process might also shed some light, valuable for historians including amateur historians, on the question about Watergate often scanted even in good histories of Watergate. Why was the Democratic National Committee headquarters broken into in the first place?